Lt. Frederick Rolette of the Provincial Marine fought in pivotal War of 1812 battles on the Canadian side.

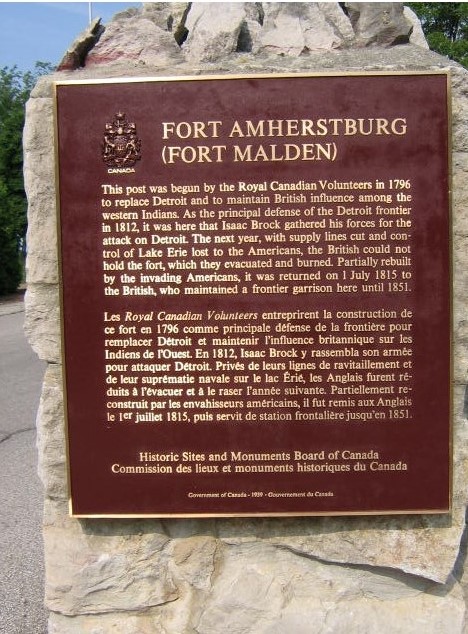

When the United States declared war on Great Britain on June 19, 1812, the British immediately seized control of Lake Erie. They already enjoyed the benefit of the Provincial Marine’s small core of war ships and generations of occupation and influence in the Great Lakes. It took several days for word of the war to reach Fort Amherstburg. When Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas St. George of the 63rd Regiment received the news, he acted promptly. On July 2, 1812, the American schooner Cuyahoga sailed up the Detroit River loaded with supplies and a military band. A contingent of sick soldiers belonging to Brigadier-General William Hull’s North Western Army followed in a smaller boat. Even though St. George knew that Great Britain and America were at war, the Americans did not.

As the Cuyahoga passed Fort Amherstburg, Lieutenant Frederick Rolette of the Provincial Marine rowed out to the ship backed by a polyglot force of soldiers, sailors and Native Americans. The surprised Americans put up only token resistance and after he fired his pistol in the air to get the Cuyahoga to heave-to, Lt. Rolette captured the Cuyahoga, although the smaller boat carrying the sick soldiers passed on unmolested to Detroit. Lt. Rolette rejoiced to discover that the Cuyahoga carried Hull’s papers outlining various plans for a campaign against Fort Amherstburg.[1]

Thomas Vercheres de Boucherville described the capture of the Cuyahoga on July 2, 1812:

At two o’clock in the afternoon a small vessel appeared sailing lightly from the open lake into the mouth of the river but the wind was unfavorable and her speed lessened somewhat. With the aid of a glass it was easily discovered that she carried the American flag and it seemed probable that her captain was unaware of the knowledge we had, that war had been declared.

Finding myself by chance in the ship yard where the Queen Charlotte was under construction, I came upon Lieutenant Frederic Rolette in the act of launching a boat manned by a dozen sailors, all well-armed with sabers and pickaxes, and I hastened to ask him where he was going with that array .”To make a capture,” he replied, as he ordered his men to row in all haste in the direction of the vessel which was slowly but steadily making her way up the river, all unconscious of the fate awaiting her.

“I asked some Indians who were standing around if they would follow that boat. They expressed their readiness for the venture and we hurriedly entered one of their canoes, our sole weapons being three guns loaded with duck shot and two tomahawks. Rolette’s boat reached the vessel’s side a few minutes ahead of us and the men boarded her without meeting any resistance.

Either the crew was unaware that war had been declared or they were uncertain of the relations between the two countries. The next instant I came up with my Indians and to leap aboard required only a moment. My friend then ran up the British flag and ordered the American Band to play “God Save the King.” I should have stated that this vessel carried all the musical instruments of Hull’s army besides much of the personal baggage of his men. This was the first prize of the war and it was taken by a young French Canadian.[2]

Lieutenant Rolette fought bravely in War of 1812 battles that often drove him onto dangerous shoals, and his pistol shot at the taking of the Cuyahoga may have been the starting shot of the war. Besides the Cuyahoga, Lt. Rolette also captured over a dozen other ships during the war, including boats and bateaux.

The capture of the Cuyahoga was not the last time that the Americans would encounter Provincial Marine Lieutenant Frederic Rolette. Lieutenant Rolette entered the Royal Navy as a young boy, was wounded at the Battle of the Nile in 1799, and also fought at Trafalgar in 1805. He took a commission as a second lieutenant in the Provincial Marine in October 1807, and commanded the Brig General Hunter until the Royal Navy arrived at Fort Malden in 1813. He also played an important role in the defense of the River Canard in July 1812 and at the capture of Detroit in August 1812. He commanded a Marine contingent during the Battle of Frenchtown in January 1813, where he once again was badly wounded.

Lieutenant Rolette Helps Capture Detroit

They refused to surrender

They chose to stand their ground

We opened then our guns

And gave them fire all around.

The Yankee boys began to fear

And their blood to run cold

To see us marching forward

So courageous and bold.

Their general sent a flag of truce

For quarter then they call:

“Hold your hand, brave British boys,

I fear you’ll slay us all.”

“Our town is at your command

Our garrison likewise.”

They brought their arms and grounded them

Right down before our eyes.

From the 1812 campfire ballad, “Come All ye Bold Canadians”

Lieutenant Rolette was present at the capture of Detroit in August 1812. On July 5, 1812, General Hull and his army arrived in Detroit and by July 12, 1812, General Hull and his forces had crossed the Detroit River between Detroit and Sandwich above Fort Amherstburg in an invasion of Upper Canada. General Hull issued a proclamation assuring Canadians that “I come to protect and not to injure you.”[3]

The American Army was twice the size of the British detachment so when the Essex Militia stationed in Sandwich met them at a bridge over the River Canard on July 16, 1812, the Americans pushed back the British. The British withdrew to Amherstburg, but General Hull worried about his supply lines and lack of heavy artillery to batter Fort Amherstburg, so he did not follow up his victory. The Americans set up camp at Francois Baby’s farm on the Detroit River and General Hull issued a proclamation that convinced about 500 Canadian Militiamen to desert. The Americans followed the British towards Amherstburg, but Canadian ships anchored near the mouth of the River Canard and British troops and Indians stopped the Americans from advancing to Amherstburg. General Hull wanted to use his large guns against Fort Malden at Amherstburg, so he delayed the attack for two weeks while the guns were being readied.

General Hull Struggles to Supply His Army

The British were not yet strong enough to push the Americans off Canadian soil, so they focused their military efforts against Hull’s supply lines. Groups of British regulars, Canadian Militia and Indians fanned out from Fort Amherstburg, jeopardizing American communication and supply lines on the west bank of the Detroit River. They attacked two key American supply lines and in early August 1812, Captain Henry Brush led an American relief column from the River Raisin in Monroe to Detroit, bringing in cattle and other supplies to General Hull’s Army. Captain Brush sent a messenger to General Hull who was encamped at the Canadian town of Sandwich, near present day Windsor, Ontario. The message advised him that Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and some of his warriors had crossed the Detroit River and advanced to the vicinity of Brownstown, and that British regulars were probably escorting and advising him.[4]

The American casualties in the Battle of Brownstown included 18 men killed, 12 wounded and 70 men missing. The Indians lost one chief. The skirmish outside of Brownstown did not turn the tide of the war, but it did reveal that the American supply line to Ohio was not secure and convinced General Hull that the British and Indian forces outnumbered him, a conviction that would ultimately lead to the surrender of Detroit to the British.[5]

Adam Muir and Tecumseh at Monguagon

For days after the Battle of Brownstown, the British forces stayed in place, anticipating another American force that had not materialized. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas St. George had sent in reinforcements so that now the British numbered nearly four hundred, but days of inactivity and depleted rations had caused Adam Muir to order his force back into their boats and return to Fort Malden. Suddenly, Tecumseh galloped up and told Muir about another detachment of Americans approaching. Tecumseh planned another ambush, this time close to the Indian village of Monguagon. The odds seemed to be in favor of the 600 American soldiers, including an artillery unit which would be pitted against Muir’s 400 British militiamen and Tecumseh’s Indian soldiers.[6]

On August 8, another American force marched toward Monroe on a mission to reach Hull’s supply train at River Raisin and escort it to Detroit. Near Monguagon, American Scouts ran into the British and Indian force of about 400 men, led by Captain Adam Muir and Tecumseh. The British and Indians blocked the road south and Lieutenant Colonel James Miller quickly mustered his Americans. In a running battle, the Americans drove the British and Indians back through Monguagon until the British retreated across the Detroit River in canoes and rowboats.

During the following week, Major General Isaac Brock, acting Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada docked at Amherstburg with reinforcements. The deserting militiamen returned and Tecumseh and Brock designed a plan to attack Detroit. The British reoccupied Sandwich and started to shell Detroit. On August 16, they crossed the Detroit River and the British and Militia fanned out to the southwest of Detroit and Tecumseh’s native warriors scattered into the woods west and north of Detroit. Their combined strength- approximately 2,000 strong-almost matched the strength of Hull’s remaining forces. A thoroughly demoralized Hull surrendered Detroit on August 16, 1812.

Hull’s surrender gave the British several unanticipated advantages. The British confiscated cannons, muskets and supplies stored at Detroit to equip and feed the Canadian Militia and their Indian Allies. The lack of an American Army reduced the threat to Fort Amherstburg and southwest Upper Canada and paved the way for the British and Canadians to occupy Michigan territory. Now that Brock had secured his flank, he could shift his forces away from the Detroit River region to the Niagara Frontier. Colonel Henry Procter of the 41st Regiment inherited Brock’s command and a military conundrum: how to hold Detroit and Michigan territory with very limited forces – the very same question that Hull had pondered.

Captain Brush asked General Hull to send him troops from Detroit to protect his supply column and on August 4, 1812, Major Thomas Van Horne, commander, and 200 Ohio militia marched south down the road they had just cut through the Black Swamp to bring supplies to Detroit. As Major Van Horne and his men crossed Brownstown Creek, three miles north of the village, Tecumseh and 24 of his Indian combatants ambushed one of the supply columns. Amidst the confusion of crackling rifles, flitting shadows and revolving battle lines the Americans began to retreat. The Indians chased the Americans as far as the Ecorse River before they melted into the woods and the Americans returned to Detroit.

The American casualties in the Battle of Brownstown included 18 men killed, 12 wounded and 70 men missing. The Indians lost one chief. The skirmish outside of Brownstown did not turn the tide of the war, but it did reveal that the American supply line to Ohio was not secure and convinced General Hull that the British and Indian forces outnumbered him, a conviction that would ultimately lead to the surrender of Detroit to the British.[7]

For days after the Battle of Brownstown, the British forces stayed in place, anticipating another American force that had not materialized. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas St. George had sent in reinforcements so that now the British numbered nearly four hundred, but days of inactivity and depleted rations had caused Adam Muir to order his force back into their boats and return to Fort Malden. Suddenly, Tecumseh galloped up and told Muir about another detachment of Americans coming. Tecumseh planned another ambush, this time close to the Indian village of Monguagon. The odds seemed to be in favor of the 600 American soldiers, including an artillery unit which would be pitted against Muir’s 400 British militiamen and Tecumseh’s Indian soldiers.

On August 8, another American force marched toward Monroe on a mission to reach Hull’s supply train at River Raisin and escort it to Detroit. Near Monguagon, American Scouts ran into the British and Indian force of about 400 men, led by Captain Adam Muir and Tecumseh. The British and Indians blocked the road south and Lieutenant Colonel James Miller quickly mustered his Americans. In a running battle, the Americans drove the British and Indians back through Monguagon until the British retreated across the Detroit River in canoes and rowboats.

General Hull Surrenders Detroit

During the following week, Major General Isaac Brock, acting Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada docked at Amherstburg with reinforcements. The deserting militiamen returned and Tecumseh and Brock designed a plan to attack Detroit. The British reoccupied Sandwich and started to shell Detroit. On August 16, they crossed the Detroit River and the British and Militia fanned out to the southwest of Detroit and Tecumseh’s native warriors scattered into the woods west and north of Detroit. Their combined strength- approximately 2,000 strong-almost matched the strength of Hull’s remaining forces. A thoroughly demoralized Hull surrendered Detroit on August 16, 1812.

Hull’s surrender gave the British several unanticipated advantages. The British confiscated cannons, muskets and supplies stored at Detroit to equip and feed the Canadian Militia and their Indian Allies. The lack of an American Army reduced the threat to Fort Amherstburg and southwest Upper Canada and paved the way for the British and Canadians to occupy Michigan territory. Now that Brock had secured his flank, he could shift his forces away from the Detroit River region to the Niagara Frontier. Colonel Henry Procter of the 41st Regiment inherited Brock’s command and a military conundrum: how to hold Detroit and Michigan territory with very limited forces – the very same question that Hull had pondered.

Battles of the River Raisin

The muffled drums sad roll has beat,

The soldier’s last tattoo!

No more on life’s parade shall meet

that brave and fearless few;

On fame’s eternal camping ground,

Their silent tears are spread

And Glory guards with solemn round

the bivouac of the dead.”

Theodore O’Hara

The Bivouac of the Dead

The Americans did not allow Hull’s surrender to demoralize them. They built a second North Western Army with William Henry Harrison, Governor of Indiana Territory, in command. Governor Harrison planned a winter campaign to regain lost territory and to attack the British at Amherstburg, hoping that ice on the Detroit River would encase the British vessels and serve as a bridge for his 4,000- man army. General Harrison and the British commander, General Procter, and their forces clashed at the Battle of Frenchtown on January 22, 1813. Although the battle was hard fought with heavy losses on both sides, especially of Kentucky volunteers, Procter and his troops prevailed. The next day the Indians massacred wounded American prisoners, creating enough American outrage to ensure their inevitable defeat. A detachment of the Provincial Marine, numbering 28 men of all ranks and acting as artillerymen actively participated in the Battle of Frenchtown. They suffered over 50 percent casualties with one man killed and sixteen wounded.[8]

A story in Michigan Pioneer Collections tells the reaction of an old Indian living in Frenchtown to the Kentucky troops. He had previously fought in the battles between the Indians and the Ohio troops under General Edward Tupper and soldiers from the same unit came to fight at Frenchtown. He exclaimed, “Huh, Mericans come. Suppose Ohio men come. We give them another chase.”

He walked to his cabin door, smoking, apparently unconcerned and looked at the troops forming the battle lines. Then he looked again. “Kentuck, by God!” He picked up his gun and fled into the woods.[9]

The Battle of Lake Erie

Sunset at the Amherstburg Navy Yard by Peter Rindlisbacher. After their defeat in the Battle of Lake Erie, the British moved their new Upper Lakes naval base to Penetanguishene on Lake Huron.

The British had to control Lake Erie to win the War of 1812, and they faced a severe supply problem in maintaining this control. The region around Lake Erie and the Detroit River did not produce enough crops and livestock to feed General Procter’s troops, the British sailors on Lake Erie or the multitude of Tecumseh’s warriors and their families gathered at Amherstburg. The British maintained their control of Lake Erie from June 1812 until July 1813, when the American fleet that Commodore Perry was building at Presque Isle became a deciding factor in the War.

In the spring of 1813, the Provincial Marine proved itself once again as an effective transport service when it carried General Henry Procter’s force of Regulars and Militia across Lake Erie to besiege the American base of Fort Meigs in Perrysburg, Ohio. Over 500 Regulars embarked on the Queen Charlotte, General Hunter, Chippewa, Mary, Nancy and Miamis, and 462 Essex Militia were loaded onto numerous bateaux. The Marine also shipped large stores and large caliber cannons to bombard the fort. The operation and one later in July did not defeat the Americans, but the officers and men of the Provincial Marine were an important part of the campaign.

On September 10, 1813, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry led a fleet of nine American ships to defeat a squadron of six British warships at the Battle of Lake Erie in Put-in-Bay, Ohio. This was the first unqualified defeat of a British naval squadron in American history.

Lt. Rolette recovered sufficiently enough to take part in the Battle of Lake Erie and took over command of the Lady Prevost when the Royal Navy Commander Lieutenant Edward Buchan was incapacitated. Severely wounded in the Battle of Lake Erie, Lt. Rolette spent the rest of the war in an American prisoner of war camp.

A Canadian Arctic Offshore Patrol Ship Named in Lt. Rolette’s Honor

At the end of the war, Lt. Rolette returned to Quebec City and his fellow citizens gave him a hero’s welcome and a fifty-guinea sword of honor in recognition of his meritorious service to his county. Never completely recovering from his many battle wounds, 46-year-old Lt Rolette died on March 17, 1831. He is buried in Saint Charles Cemetery in Quebec City.

In 2015, the Canadian national defense minister Jason Kenney announced that an Arctic Offshore Patrol ship was named in honor of Lt. Rolette in recognition of his service to his country. Jeff Watson, parliamentary secretary to the minister of transport and member of parliament from Essex, Ontario made a parallel announcement in Windsor, Ontario.

According to his naval biography, there is no known image or painting of Lieutenant Rolette, but the Canadian government named an Arctic Offshore Patrol Ship in his honor

References

[1] Milo Milton Quaife, editor. War on the Detroit: The Chronicles of Thomas Vercheres de Boucherville and the Capitulation by an Ohio Volunteer (Chicago: The Lakeside Press, R.R. Donnelley & Sons, Co., Christmas 1940) p. 77-78.

[2] . A biography of Frederick Rolette is included in the biographies on the River Raisin Battlefield Website.

[3] James J. Talman, Basic Documents in Canadian History (Toronto: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1959)p. 78.

[4] The Battle at Brownstown: American and British accounts, Columbian Centinel, September 12, 1812. Parks Canada Teacher Resources Centre: file://A:\americanindians_1812_htm

[5] Ibid.

[6] Alec R. Gilpin, The Territory of Michigan, 1805-1837 (Michigan State University Press, 1970)p. 13-32.

[7] Alec R. Gilpin, The Territory of Michigan, 1805-1837 (Michigan State University Press, 1970)p. 13-32.

[8] The American Invasion of Canada: The War of 1812’s First Year. Pierre Berton.

[9] Michigan Pioneer Collections, 1907. “The River Raisin Massacre and Dedication of Monuments,” 1907, p. 210.

Sandy Antal. A Wampum1998. Denied. Carelton University Press, 1998.

Alec R. Gilpin, The Territory of Michigan, 1805-1837 .Michigan State University Press, 1970

John R. Elting, Amateurs, To Arms! A Military History of the War of 1812. Chapel Hill, N.C., 1991.

Donald R. Hickey. Don’t Give Up the Ship! Myths of the War of 1812. University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Ralph Naveaux. Invaded on all Sides. The River Raisin National Battlefield Park Visitor Center.

Michigan Pioneer Collections, 1907. “The River Raisin Massacre and Dedication of Monuments,” 1907, p. 200-238.

The War of 1812 Website, Bob Garcia Paper.

Ontario History, Volumes 9-12 by the Ontario Historical Society.

“We Lay There Doing Nothing”: John Jackson’s Recollection of the War of 1812 Edited by Jeff L. Patrick. Indiana Magazine of History.