Many pioneers settling along the banks of rivers running into Lake Erie, including the Detroit River and the River Raisin, considered the marshes at their mouths obstacles that needed to be removed or at best, ignored because they were not tillable or habitable land. William Clark Sterling of Monroe, Michigan viewed the marshes at the mouth of the River Raisin as hunting and marine assets that could be utilized and should be preserved. His passion for hunting, sculling, and yachting impelled him to work to preserve the marshes that eventually were included in the park that Monroe citizens named for him, Sterling State Park.

The only Michigan state park on Lake Erie, Sterling State Park is located in Frenchtown Charter Township in Monroe County, north of where the River Raisin empties into Lake Erie. Although it is dedicated to marshland, the park includes a beach, a boat launch, shore fishing and over six miles of biking and hiking trails.

Timeless Marshes Before William Sterling’s Marsh Time

Seventeenth Century Coeur de bois, French runners of the woods, and Eighteenth Century voyageurs explored and utilized the marshes between the River Raisin and the western end of Lake Erie, marshes that the Native Americans had hunted and fished for generations. The Coeur de bois and voyageurs also hunted the marshes for food and fur bearing animals and fished their waters. As Nineteenth Century farms and villages and cities spread throughout Monroe and Monroe County, many settlers considered the marshes and wetlands obstacles, but a few hunters and fishermen appreciated what the wetlands had to offer.

In 1849, a year before William’s birth, Harvey M. Mixer, a friend of William’s father Joseph Sterling, worked as a buying and shipping agent for the lumber business, visiting Monroe at least three times a year. He discovered the pleasures of shooting in the marshes surrounding the mouth of the River Raisin in Monroe and he always brought his gun with him. Every fall, thousands of ducks, geese, and swans flocked to feed on the wild rice and wild celery growing throughout the marshes. Harvey Mixer reported seeing no other human except occasionally a Frenchman pushing his dugout through the wild rice. He didn’t hear gunshots for days. He also reported excellent shooting on the margins of the marsh, and that in one afternoon he and a friend bagged 73 English snipe. He said that on the high ground in Monroe back a few miles from Lake Erie, quail, wild turkey, partridge, and other game birds were abundant.

In the fall of 1853, when William Sterling was about three years old, Harvey M. Mixer sent his schooner West Wind to Monroe with a cargo of iron for the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad which was then constructing a line from Monroe to Chicago. Harvey Mixer chartered the West Wind back to Buffalo with a cargo of corn, but he added his own imaginative touch to the cargo. A crowd gathered when the West Wind anchored at her dock to admire the numerous ducks that Harvey had trussed on the rigging to advertise the results of his three days of autumn shooting. The number of ducks so inspired Harvey Mixer’s friend, John L. Jewett (known as Jack) that the next year he and some other mutual friends George Truscott and J.H. Bliss of Buffalo all traveled to Monroe for the autumn hunting season. They found lodgings with Joe Sears, who had a house on an island in the middle of the marsh large enough to accommodate their boats, decoys, and provisions and they hunted, enjoyed some of the finest bass fishing in the country, and they discussed how they could make their hunting and accommodations permanent.

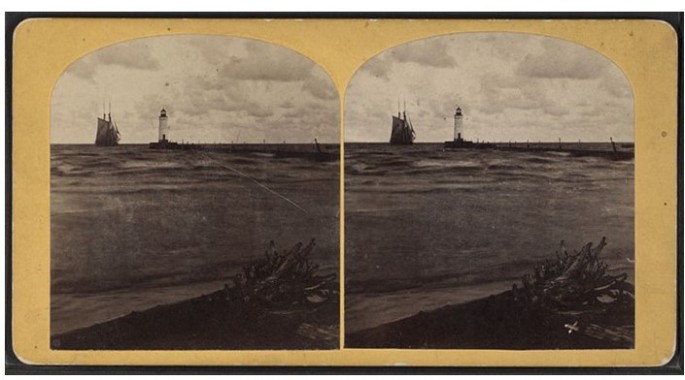

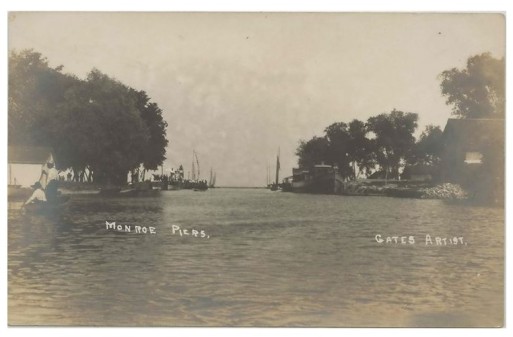

When the group of hunters returned to Buffalo, they conferred and J. L. Jewett. J.H. Bliss, George Truscott, A.R. Trew, and H.M. Mixer decided to buy the facilities at the Monroe piers located directly across the channel from the government piers and the shooting ground to establish a clubhouse and hunting preserve. A few years earlier, the Michigan Southern Railroad had built two or three state of the art steamers to connect the eastern end of the line with Monroe piers with Buffalo. The railroad had built docks, warehouses, elevators, machine shops, and a large hotel. The men decided to lease the property with permission to use the docks and other buildings as long as they lasted.

In 1854, the group of sportsmen organized a hunting club that they christened the Golo Club, with officers John L. Jewett, president; J.M. Sterling, vice-president; H.M. Mixer, secretary and treasurer; and directors George Truscott, J.H. Bliss, and A.R. Trew. The founders of the Golo Club decided to adopt the name that one of their French marsh guides had bestowed on a duck with peculiar markings that they occasionally shot in the marsh. Some club members called the duck which had a black back, glossy black wings tipped with white, and a black head and about the size of a redhead, a whistler because of the loud whistling noise it made in flight. Their French guide called the whistler a Golo and the club members adopted the name for their club.

The Golo Club didn’t have title to any of the marsh lands, but the members operated under permits from the United States government to occupy the lighthouse reserve where the clubhouse stood and they obtained leases and shooting privileges from the old French settlers. People respected the club as a private reserve, but its members didn’t prohibit other hunters from shooting in the marshes. By the 1865 hunting season, the Golo Club members and their friends averaged about forty ducks a week, over 3,000 ducks for the 1865 season. They shipped ducks in specially made baskets to customers and friends in New York Cleveland, and Detroit. By this time, Joseph M. Sterling was the only surviving original club member, and although he didn’t shoot extensively, he performed other valuable services for the club.

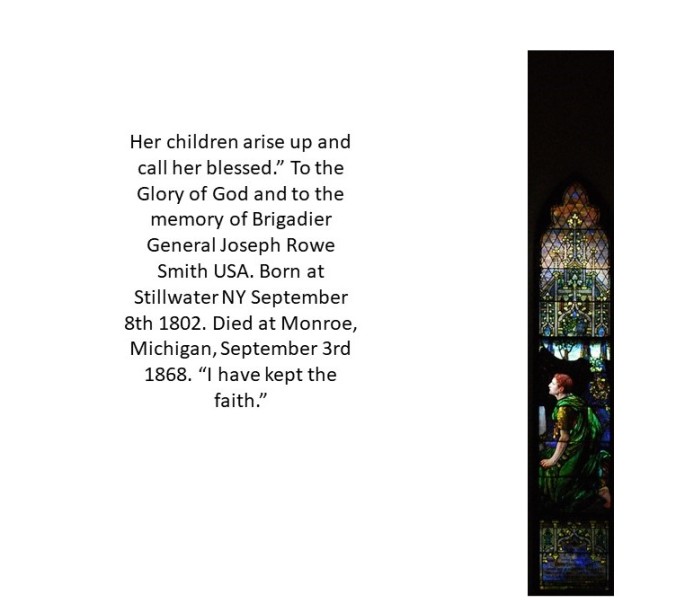

By 1866, Harvey Mixer’s business kept him mostly in New York, and he sold his share of stock to General George A. Custer, who had returned to Monroe at the close of the Civil War. After the U.S. Army ordered General Custer and his command to Texas, he sold his stock to Honorable H.A. Conant of Monroe. The Golo Club existed for a few more years, but members moving to other places, deaths, and the loss of the club house in a violent wind storm caused its demise.[1]

William Clark Sterling, Sr. Follows in His Father’s Business Footsteps

William Clark Sterling Sr. was born on September 17, 1849 in Monroe to Joseph Marvin Sterling and Abby Clarke Sterling. The 1870 United States Federal Census shows William Clarke Sterling living in Monroe with his father Joseph, 51, his mother Abbe E., 45, his sisters Mattie E. 22, and Emma, 10, and his brothers Joseph 18, Frank, 16, and Walter, 13. He listed his employment as a clerk in an office.

On February 21, 1871, William Clark Sterling married Ada E. Calhoun in Monroe. Ada, the daughter of Erastus and Lucinda Calhoun, was born in New York in 1854, and she came to Monroe with her parents at the age of 12. She and William had four children: William C; Abbie L.; Nellie L, and Ada Mae. The 1880 United States Census recorded William married to Ada and living in Monroe with their children: Willie, 8; Abby, 6; Nellie, 5; and Ada M, age 3. Ada died on April 25,1894 in Detroit, at age 40 and the 1900 Census showed William, age 50, a widower, living in Monroe with his daughters Abbey, Ada and Nellie.

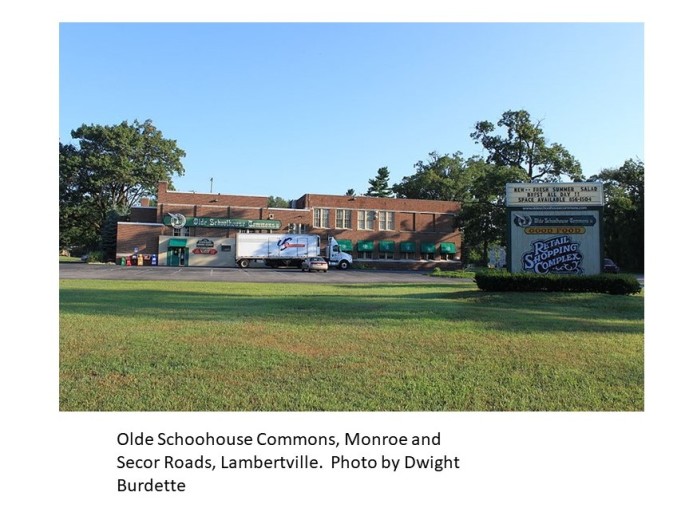

Early in his life, William Clark Sterling, Sr., followed in his father’s business footsteps. In 1847, Joseph Marvin Sterling began using steamers to ship coal packed in hogsheads and barrels for blacksmiths to Monroe, paving the way for employment for his sons and the Sterling Manufacturing Company. In the fall of 1848, Joseph built his first coal shed in Monroe, stocking it with forty tons of blacksmith and grate coal estimated to last more than a decade. Business steadily increased until by 1860, nearly two hundred tons were used in Monroe. By 1865, Joseph’s coal total had increased to 400 tons, and by 1870 over 1,200 tons were sold and burned. The tonnage had increased to nearly 3,000 tons by 1880 and the receipts of coal at the Monroe station for 1888 amounted to over 500 carloads or nearly 10,000 tons.

As the years passed, William Clark Sterling, dealer in coal, wood, salt, hay, straw and ice handed these transactions at the same location his father Joseph Marvin Sterling had built his first coal sheds in the fall of 1848. William Clark Sterling along with his brothers and father was instrumental in incorporating The Sterling Manufacturing Company in January 1888, with a capital stock of $10,000. In 1887, the incorporators had begun building their plant, consisting of a saw, shingle, lath, and planing mill with engine power and yard room. The Sterling Manufacturing Company operated as general contractors and builders and eventually built over 30 houses in Toledo, besides a large number in Monroe and Wayne counties. The Sterling Company docks with the pole dock of F.S. Sterling & Company provided the only Monroe landing for boats drawing over seven feet of water.[2]

William Clark Sterling, Sr. Grows up to Love the Marshes

During William Sterling’s growing up years in Monroe, he noted his father’s activities in the Golo Club and the fowling and fishing in the River Raisin marshes. Hunters came to the marshes in increasing numbers every year to shoot canvas backs, redheads, mallard, and teal. Market hunters in Monroe marshes sold wild fowl by the hundreds for 25 to 50 cents each. Hunters pushed both fall and spring shooting to the limit and year by year, the numbers of water fowl that early hunters had watched stretch in thick ropes across the sky, dwindled to thin strings and swirls.

Growing up under the tutelage of his father Joseph, William became a passionate hunter. In 1878, he began buying the nearby marshland for as little as 30 cents an acre because more than most people he understood the value of wetlands to humans as well as wildlife.

For the second time in half a century, a group of sports shooters organized to regulate their shooting, only this time in Syracuse, New York, instead of Buffalo, with different participants. On May 30, 1881, a group of 24 gentlemen from the United States and Canada gathered in the Globe Hotel in Syracuse, New York, to conduct some important business that would profoundly affect the Monroe marshes.

The men organized the Monroe Marsh Company, elected Howard Soule chairman and H.G. Jackson secretary and agreed to purchase about 5,000 acres of marsh lands. Like his father had done in the Golo Club, William Sterling joined the Monroe Marsh Company and worked to preserve and improve the wild fowl hunting and fishing and pass down the privilege to future generations. He came a member of the Monroe Marsh Company in 1901 and remained active in the Company for years.

William Clark Sterling, Sculler and Commodore

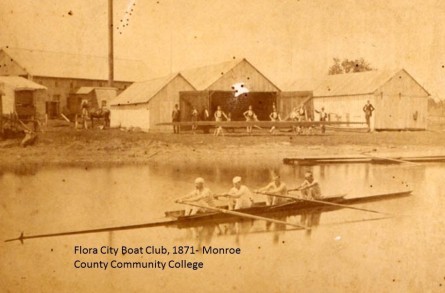

In 1869, rowing clubs from Toledo, Detroit, Saginaw, Milwaukee, and Erie, Pennsylvania, formed the Northwest Amateur Rowing Association. Monroe had more than its share of enthusiastic young men eager to participate in races, but no available racing shells. The only possible candidate was a lap -streak boat about twenty feet long called the Kate Johnson, which had a checkered past. During the Patriot War, Kate Johnson, the daughter of William Johnson had used the boat to carry provisions to her father who hated the Canadian government. Both the Canadian government and the United States government had offered a reward for his capture because he and his men had burned the Canadian steamer Sir Robert Peel. The boat had been presented to Joseph Marvin Sterling, William’s father, and he had kept it and treasured it since then.

Several young men from Monroe obtained the boat from Joseph Sterling and fitted her out as a double scull. Organizing under the name of the Independent Boat Club of Monroe, they entered the revamped boat against the modern racers in the first regatta of the Northwestern Amateur Rower’s Association at Toledo, Ohio, on July 8, 1869. William C. Sterling and William Calhoun were the crew. The two Williams attracted an enthusiastic crowd that cheered them on in Toledo, and although they didn’t win the regatta, they generated enough enthusiasm to convince its citizens that Monroe needed a rowing club.

Interest in rowing continued to grow and in February 1871, the Floral City Boat Club organized and purchased a six-oared lap streak they christened “The Atlanta.” In 1873, a newly formed club “The Amateurs” joined the Floral City Boat Club in a regatta on the River Raisin, pitting their new four-oared lap streak “The T.N. Perkins, against “The Atlanta.” The Perkins won the victory flag. On July 22, 1874, the Floral City crew won the Northwestern Regatta at Toledo. William Sterling rowed on several crews and participated in and won races and regattas for the Monroe teams.

When the Monroe Yacht Club was organized, and incorporated on May 27, 1887, William Clark Sterling was named its first Commodore and his brother Joe C. the treasurer. The schooner Emma G. is named on the list of Monroe Yacht Club vessels and Joe C. et al is listed as the owner.[3]

Sterling State Park

William Clark Sterling died on August 26, 1924, and he is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Monroe. Rowers, yachtsmen, and other Monroe citizens remembered William Clark Sterling’s efforts to conserve and intelligently manage the River Raisin marshes, and in 1934, ten years after his death, a group of Monroe citizens worked to preserve 115 acres of marshland north of the River Raisin as a park named in his honor. It was officially dedicated and named Sterling State Park in 1935. The only Michigan park on Lake Erie, Sterling State Park is considered a gateway park, since it is often the first stop for out of state visitors.[4]

For decades, pollutants from the Detroit River were deposited in the region of the park, killing huge numbers of fish and wild life and making the western part of Lake Erie unsuitable for water activities like swimming and boating. In the late 1990s, the Environmental Protection Agency declared the park area and the Detroit River and western end of Lake Erie an area of environmental concern because of the level of pollutants in Lake Erie and the River Raisin, with the level of PCBs in fish from the area increasing 87 percent from 1988-1998.

Much of the pollution resulted from the industrial growth of the River Raisin delta and Lake Erie, including a nuclear power plant to the north and the largest industries including a Ford plant and the coal-burning Monroe Power Plant to the south both severely impacting the area ecosystem. In 1997, Ford completed its environmental dredging project in the River Raisin, removing about 25,000 cubic yards of toxic PCB- contaminated sediment from the River Raisin.

In 2001, the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge included Sterling State Park as its southern border, allowing the park to receive federal funding for a $12 million-dollar renovation project. The remodeling included miles of public wetland a six-mile system of paved walking and biking paths, many lagoons and marshes furnishing habitat for wildlife and birdlife, and a 47-acre camp ground on the higher ground of Lake Erie overlooking the widest section of beach in the park. The renovation included upgrading Sterling Marsh Trail, which loops for three miles around the park’s largest lagoon, passing a tower, observation deck and interpretive area dedicated to viewing wildlife.

The lagoons attract many different varieties of water birds, among them great blue herons, mergansers, Canada geese and smaller shorebirds. Slender white egrets, standing more than 30 inches high, stand sentinel in the lagoons beginning in late March and staying until mid-November and great blue herons fish in seclusion.

It’s not difficult to imagine William Clark Sterling standing on shore admiring them.

Notes

[1] History of Monroe County Michigan: a narrative account of its historic progress, its people, and its principal interests. John McCelland Buckley, Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1913. p. 459-463.

[2] History of Monroe County Michigan: a narrative account of its historic progress, its people, and its principal interests. John McCelland Buckley, Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1913. p. 459-463.

[3] History of Monroe County, Michigan. Talcott Enoch Wing,. New York: Munsell & Company, 1890. pp. 406-414.

[4] Michigan Trail Maps. http://www.michigantrailmaps.com/member-profile/3/118/ 0