Marie Mackintosh hugged the Detroit River as close to her heart as she did her parents Angus and Mary Archange Baudry, dit Desbutes, dit Saint-Martin Mackintosh, and her 13 brothers and sisters. The clear, calm river flowed a few feet away from her home and her father’s store and storehouse on its banks on the Canadian side near present day Windsor, Ontario. Marie’s father, Agnus Mackintosh, had purchased the land on the south bank of the Detroit River in 1796, shortly after the British had finally evacuated Detroit as they had agreed to do at the end of the Revolutionary War. He built a complex containing a store, a wharf, a storehouse and a rambling frame house on Sandwich Street, a few miles east of the home of John Davis to shelter his family and his business. He named their home Moy House and Marie often heard him telling is friends that even though his home stood east of Sandwich, it was the meaty center of the sandwich, not the outside crust.

Sandwich Town and Detroit City shared an interwoven history. Around 1796, Detroit celebrated its independence from British rule and British government moved across the Detroit River to Sandwich Town, which had been chosen as an administrative center and capital of Upper Canada (Ontario) to replace the original offices at Fort Ponchartrain in Detroit. When the British government officials left Detroit for Sandwich, they took hundreds of British loyalists with them, including lawyers, constables, and merchants like Angus McIntosh and his family.

The War of 1812 brought famous military leaders from both sides to Sandwich, including British General Isaac Brock, American Generals William Hull and William Henry Harrison, and Native American warriors like Tecumseh and Walk-in-the-Water. The War of 1812 also set the stage for the tragedy of Marie and her Canadian soldier.

Every night Marie walked along the riverbank and down her father’s wharf to watch the sunset dying the Detroit River into drops of many colors. She walked between the fruit trees that bloomed on both the Canadian and American sides of the water. Apple, mission pear, cherry and plum trees blossomed in spring, filling the air with their fragrance and offering fruit in the summer and fall. Sometimes in winter, Angus burned apple wood in the fireplace and its fragrance filled the house. On her Detroit River walks, Marie made her way through wild flowers and often saw deer in the surrounding woods and otter and muskrat along the River banks.

Every night while Marie watched the sunset over the Detroit River she thought about her sweetheart, a Canadian soldier with the British and Canadian forces stationed in Windsor. .[1] The narrator of Maria’s story in Legends of Detroit identifies Maria’s sweetheart as Captain Muir, but Captain Muir doesn’t fit into the narrative of the Battle of Monguagon and Marie’s part in its aftermath, because he survived. A Lieutenant Charles Sutherland also fought in the battle, and he was wounded and he later died. Could her lover have been Lieutenant Sutherland?[2]

Whether his name was Muir or Sutherland, or Brown, Marie loved the young Canadian officer who so far had been too timid to declare his love and ask for her hand in marriage. She thought about him constantly as she gazed over the calm waters of the Detroit River, turning over ways of making him brave enough to declare his love in her mind like she turned over stones on the sandy shores of the Detroit River. She waited through the spring and early summer for the Canadian officer to summon enough courage to speak his mind and heart to her.

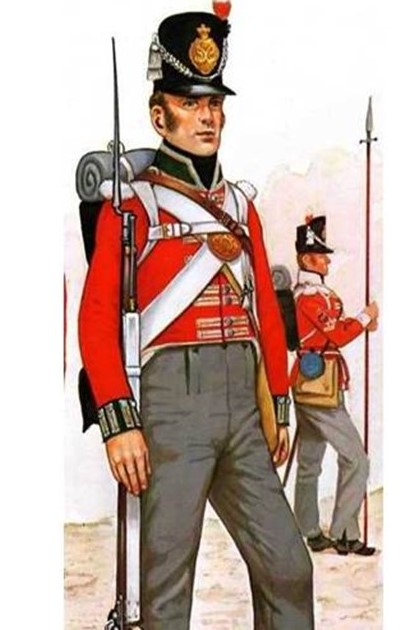

While Marie waited for her Canadian officer to speak his mind, soldiers manning war canoes and larger vessels gathered on the banks of her Detroit River, determined to speak their minds and resolve the war between Great Britain and the United States and their Native American allies on each side. American General William Hull encountered the task of opening and defending a road between Detroit, Monroe, and Ohio to keep his Army supplied. The 200 men of the 41st Regiment, 300 men of the Canadian Militia and the 50 soldiers of the Newfoundland Fencibles based at Amherstburg were equally determined to prevent his Army from receiving supplies and reinforcements. The Americans had lost their first attempt to move supplies down Hull’s trace at the Battle of Brownstown on August 5, 1812, even though they outnumbered the British and Canadians 8 to 1.

The Canadian Captain knew that the British and Canadian Army were planning a return engagement to keep the Americans in Detroit from receiving supplies and he knew that he would be a part of it. His knowledge gave him the courage to make a decision. He would declare his love to Marie and ask for her hand in marriage. After all, he could fight more effectively and courageously if Marie gave him her word and waited impatiently for him back in Sandwich. Her yes would propel him to certain victory in battle.

Anticipating her smile and her joyous acceptance of his proposal, the Captain journey to Moy and to his delight, found his lady love walking alone in the garden, an achievement in itself considering the size of her family and household. The Canadian Captain fired a fusillade of impassioned words at Marie’s heart, and held out his arms, expecting her to fall limply into them in surrender. Marie didn’t surrender. Instead, she looked at him cool as the ice on the winter River. “You took so long to speak that I no longer choose to hear what you are saying,” her glance told him. Her eyes glinted like chips of Detroit River ice when he asked for her hand in marriage. Then she laughed at him.

The Canadian officer hadn’t known how to melt the ice in Marie’s eyes and heart, but her laughter slashed his pride. He turned abruptly and ran from Marie and Moy House, possibly reasoning that battle would be a much safer choice than laughter from his sweetheart Marie. For her part, Marie couldn’t believe that he given up so easily. “He’s only piqued,” she thought. “He certainly must know that I love him. Why must men be so stupid and matter of fact, taking months to make up their minds to woo a girl? Then if she doesn’t immediately say yes, they let their wounded pride get in the way of a satisfactory answer. He’ll be back, she thought. He will certainly return.

The Canadian Captain did not return. Marie waited with all of her senses straining to hear his footsteps, but all she heard was silence. She felt a heart throb of alarm and hurried to the door. She called her Canadian Captain, but she heard only the mocking echo of his horses’ hooves as he galloped away. She called louder, she screamed, but he disappeared down the street in a flurry dust.

For the remainder of that day, thick clouds of impending doom choked Marie’s heart and mind. The clouds thickened when her father told her that a battle had taken place across the Detroit River in Monguagon. She sat late in front of the fireplace, hoping, praying that her lover’s anger would cool and he would return. She sat lonely by the fire until its dying embers prodded her into going to her room and bed. She got into her curtained four poster bed and pulled the comforter up over her chin, but she couldn’t escape into sleep. Through the long ominous night hours, she despaired and often pounded her pillow. How could I have not told him of my feelings? She reproached herself, but then immediately reproached her lover. How could he not sense my feelings and understand how I wanted him to express his feelings?

Finally, toward morning, exhausted by her aching heart and her tears and questions with no satisfactory answers, Marie fell asleep. Muffled footsteps interrupted her uneasy slumber and sitting bolt upright, she pulled the curtains aside. Bright moonlight shone through her window and outlined the shape of her Canadian officer lover standing beside her bed. Inching closer to the edge of the bed to see him better, Marie saw with a heart stopping alarm that his face gleamed white as a corpse in the moonlight and blood oozed from a gaping wound in his forehead.

Before Marie could do more than tremble with fear and will herself to wake from the nightmare, her lover spoke to her. “Don’t be afraid, Marie. I came to tell you, I fell tonight in battle, shot through the head, and my body lies in a thicket on the battlefield. If you love me at all, I beg you to rescue my body from the hands of hostile Indians and from the wolves and beasts of the forest. I assure you that the Americans will not long exult. Traitors sit around their camp fires and listen to their councils. Our blood has not been shed in vain. The standard of old England will float again over Detroit. Farewell, may you be happy.”

As her Canadian officer spoke, he picked up her right hand and held it. A chilling sensation, colder than Detroit River ice and winter winds, cold as the grave, raced through her body. Marie fainted.

Marie awoke to the warmth of sunlight fingers touching her face and flooding her room as brightly as the moonlight had flooded it the night before. She jumped out of bed and quickly pulled on her corset and petticoats and dress. The night before! The night before had to have been a terrible nightmare. This very morning she would go to Colonel Isaac Brock’s camp and find her Canadian captain and tell him how she felt about him. She raised her right hand to fasten her top button and she stiffened with disbelief and fear. Her lover’s touch the night before had left his deep, dark, fingerprints on her hand. She stared at her right hand in horrified fascination. Her lover’s visit had not been a dream after all, and he had trusted her with an important mission.

Patting her hair into place with her left hand, Marie called for her horse, ordered a servant to follow her, and galloped to Sir Isaac Brock’s camp at Fort Malden. Formerly known as Fort Amherstburg, the British had built the fort in 1795 to provide a defense against any American invasion of Canada and Sir Isaac Brock and Tecumseh used it as a command post. Marie found the fort occupied by a jumble of soldiers and Indians. She soon discovered that her Canadian lover had been killed in what was called the Battle of Monguagon

American Lieutenant James Miller had assembled a 600 man strong contingent of the 4th Infantry, some militia and two pieces of artillery, a six pounder and a howitzer, to try again to reach the supply convoy waiting at Frenchtown. For their part, the British sent 150 men of the 41st Regiment of Foot, fifty militia, and about 200 of Tecumseh’s Indians to prevent the Americans from being resupplied. On August 8, 1812, the British crossed the Detroit River and established a blockade near the village of Monguagon, now Trenton. In the late afternoon of August 9, 1812, the British under Captain Adam Muir and Tecumseh fired the opening shots of their ambush and Lt. Miller quickly formed his men into a line, fired a volley, and advanced on the British with bayonets.

Second Lieutenant of Artillery James Dalliba who would later be surrendered as a prisoner of war in Canada, wrote that “The incessant firing in the centre ran diverging to the flanks. From the crackling of individual pieces it changed to alternate volleys and at length to one continued sound. And while everything seemed hushed amidst the wavering roll, the discharge of the six-pounder burst upon the ear. The Americans stood!”

The Battle of Monguagon lasted for more than two hours, with the British casualties numbering six killed and 21 wounded, and the Americans suffering 18 killed and 63 wounded. The Americans beat the British back through present day Trenton and across the Detroit River. The Indians under Tecumseh’s command retreated into the woods. Despite the American victory, Lt. Miller believed he couldn’t advance any further since he had lost 13 percent of his force, and he requested aid from General Hull to bring his injured men back to Detroit. By August 12, 1812, Lt. Miller’s soldiers returned to Detroit, their mission of hooking up with the supply train unsuccessful.

At the beginning of the War of 1812, the Michigan Wyandot fighting at Monguagon had been neutral, with both the British and American forces vying for their allegiance. Walk-in-the-Water offered his services to the Americans, but General Hull followed government policy and rejected their offer, telling the Wyandot to stay out of the fight or pay the consequences. Walk-in-the-Water and his people also did not join Shawnee brothers Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh in their efforts to halt American expansion onto Indian lands, but eventually Tecumseh and the British forced Walk-in-the-Water and the Wyandot to move to Amherstburg.

In early August 1812, Tecumseh and his leading Wyandot supporter Rouindhead, convinced the Wyandot and their head chief, Walk-in-the-Water to join the coalition of the Indians and the British. The alliance didn’t successfully drive the Americans away, but the Wyandot villages continued to block Hull’s Trace. Walk-in-the-Water fought at Monguagon, Detroit, and the River Raisin, but when General Procter evacuated the area in the fall of 1813, Walk-in-the-Water sued for a separate peace with the Americans. In 1815, Walk-in-the-Water signed the Treaty of Springwells, two years before his death in 1817.

On August 13, 1812, Major General Isaac Brock took command of Fort Malden and on August 16, 1812, he led the British troops and Chief Tecumseh and his Indian warriors across the Detroit River to march on Fort Detroit. The British and Indian force encouraged rumors that the Indian warriors were at least 5,000 strong and would swoop down on the civilian population of Detroit. General Hull surrendered Fort Detroit without firing a shot, sealing the fate of soldiers like Lt. James Miller and Lt. James Dalliba to become prisoners of war of the British. The successful siege of Detroit was pivotal in acquiring Indian support for the British at Fort Malden during the War of 1812.

Marie didn’t explain why she was at Ft. Malden in the aftermath of a battle. She didn’t stop to talk to anyone. She pushed through the crowd of soldiers and Indians, searching until she found Walk-in-the-Water, who was her father’s friend and her friend too, and she astonished him speechless by telling him the story of the Battle of Monguagon. Threatening to paddle a canoe across the Detroit River to the battlefield herself if necessary, she convinced him and a few of his warriors to take her to the battlefield. As soon as she felt the bow of the canoe hit the beach, Marie jumped out and began to search the battlefield, Walk-in-the-Water hurrying behind her. Finally, she found her Canadian Captain in a thicket, with a bullet hole in his head. She begged the warriors to help her lift his body into her canoe and they formed a solemn procession down the Detroit River to Sandwich where her lover was buried.

From the day that she found her Canadian Captain at Monguagon, Marie wore a black glove on her right hand, and every August 9, dressed as a beggar and wearing sandals, she went from house to house from Sandwich to Windsor, asking alms for the poor. Even after she married a kind man of means, she continued to honor her Canadian Captain.

The Canadian Captain also keeps an eternal vigil. Every August 9, the anniversary of his death, the ghostly Canadian Captain glides through the shady woods of Monguagon, now Trenton, headed toward the Detroit River on a perpetual journey to Sandwhich and his sweetheart Marie.

Notes

[1] The account of this legend in Legends of Le Detroit says that Maria MacIntosh’s sweetheart is a man by the name of Captain Muir, but that is mixing legend with fact, which is a characteristic of most legends. Captain Adam Muir was involved in the Battle of Monguagon, but he was wounded, not killed. A Lt. Charles Sutherland also fought, but he, too, was wounded and later died. Since this is a legend not completely verifiable by fact, perhaps Maria’s sweetheart was an officer in the Canadian Militia which also participated in the battle. In fact, the British forces at Amherstburg which would later be involved in the Battle of Monguagon consisted of 200 of the 41st (The Welch) Regiment, 50 of the Newfoundland Fencibles, 300 of the Canadian militia and a few gunners.

[2] Lieutenant Charles Sutherland joined the 41st as lieutenant from the Newfoundland Fencibles on August 25, 1810.

Sergeant‑Major Adam Muir was appointed adjutant of the 41st Regiment on September 30, 1793 and embarked in that capacity with the battalion companies.