Captain Hart’s marker is located just four tenths of a mile south of Heck Park, on the east side of North Dixie Highway, in front of Carter Lumber. The post office address is 850 North Dixie Highway, Monroe, Michigan 48162. Monroe County Historical Society. Photograph by Dale K. Benington.

Captain Nathaniel Gray Smith Hart’s Story

Nathaniel Gray Smith Hart, born in Hagerstown Maryland in 1794, probably never dreamed that he would die at the hands of a Native American near the Raisin River in Frenchtown, Michigan Territory. A Lexington lawyer and businessman, Captain Hart served with the Kentucky volunteer militia during the War of 1812 as Captain of the Lexington Light Infantry. He and many of his men died in the River Raisin Massacre on January 23, 1813 after the British and Indians had taken them prisoner the day before. News of the deaths of Nathaniel and many of his men in the two Battles of Frenchtown and the Massacre afterwards spread across the territories, states, and fledgling country and soldiers and citizens alike rallied around “Remember the Raisin” as their call to arms.

Perhaps pictures from his life flashed through Captain Hart’s mind as he lay dying in the snowy Michigan woods far from his Kentucky home.

Nathaniel’s father, Colonel Thomas Hart had fought in the Revolutionary War, and in 1794, the year of his second son Nathaniel’s birth, he moved his family to Lexington, Kentucky. A wealthy businessman, Colonel Hart and his wife Susanna Gray Hart had four daughters and three sons. The four Hart girls married well: Ann married James Brown, a United States Senator and Minister to France; Eliza married surgeon Dr. Richard Pindell a Society of the Cincinnati member; Susanna married lawyer Samuel Price; and Lucretia married Henry Clay, United States Senator and Secretary of State. Nathaniel himself married well. His wife Anna Edward Gist’s stepfather was Charles Scott, Kentucky Governor. While Nathaniel attended Princeton College, he met William Elliott from Western Ontario, whose Loyalist father had moved to Canada after the Revolutionary War. The two Princeton students became close enough friends for William to stay with Nathaniel’s family to recover from a serious illness. Captain William Elliott would not return the caring or hospitality at the River Raisin.[1]

After he returned to Lexington, Nathaniel Hart read law with his brother-in-law Henry Clay, and he passed the bar and created a law practice there. In April 1809, he married Anna Edward Gist and they had two sons, Thomas Hart Jr. and Henry Clay Hart. In a less positive parallel with the life of his brother-in-law. Nathaniel Hart dueled with Samuel E. Watson on January 7, 1812, on the Indiana side of the Ohio River, near site where Silver Creek emptied into the river. The site was the same spot where Henry clay had dueled with his fellow state legislator Humphrey Marshall in 1809.[2]

In 1812, national events changed the course of Nathaniel Hart’s life and ultimately brought him to his death on the Michigan frontier. On June 18,,1812, the United States declared War on Great Britain. On August 16, 1812, American General William Hull surrendered Fort Detroit and his 2,000 mostly militiamen to British General Isaac Brock. General Brock allowed the militiamen to return to their homes, but sent the regular U.S. Army troops as prisoners to Canada. With the British takeover of Fort Detroit, Michigan Territory was declared part of Great Britain and Shawnee Chief Tecumseh increased his raids against American positions on the frontier.

At the beginning of the War of 1812, Nathaniel Hart received a commission as Captain of the Lexington Light Infantry Company, -the “Silk Stocking Boys-” a volunteer arm of the Fayette County, Kentucky Militia. He went on to serve as Inspector of General William Henry Harrison’s Army of the Northwest. In August 1812, his command joined the Fifth Regiment of the Kentucky Volunteer Militia and it became part of the Army of the Northwest under General James Winchester.

As part of the campaign to retake Detroit from the British, General William Henry Harrison, Commander of the Army of the Northwest, arrived at the American camp on the Maumee River where he found just 300 Kentucky troops. He discovering that the remainder of the troops had left the night before with General Winchester bound for Frenchtown on the River Raisin in Michigan Territory, because the 200 Frenchtown residents had asked the American Army to protect them from an occupying British force and their Indian allies. General Harrison sent Captain Hart with orders to General Winchester to “hold the ground we had got at any rate.”[3]

The First Battle of the River Raisin

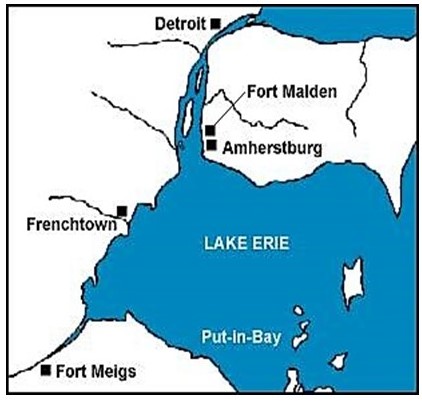

On January 18, 1813, Canadian Major Ebenezer Reynolds, 200 Canadian militia and Indian Chiefs Round-Head and Walk-in-the Water along with a positioned howitzer waited in Frenchtown for the arrival of the Kentuckians. Some accounts of the battle state that Shawnee Native American leader Tecumseh was present at the battle, but left before the massacre and others say that he commanded the Indians from afar. Kentuckian Lt. Colonel William Lewis commanded 660 men without artillery. They crossed solidly frozen Maumee Bay at the western end of Lake Erie and advanced on Frenchtown. At Frenchtown, the Kentucky troops crossed the frozen solid River Raisin under withering Canadian and Indian musket fire and formed a line of battle.

They charged gallantly up the river bank, leaped the pickets, dislodged the Canadians and Indians, and drove them into the surrounding forests. The Kentuckians pursued the fleeing Canadians and Indians into the forest and the fighting continued from 3 o’clock until dark. The Kentuckians decisively won the battle, with casualties of 12 killed and 55 wounded. The Canadians and Indians retreated 18 miles to Malden, leaving 15 dead in the open field and carrying away their wounded.

That evening the Kentuckians returned to Frenchtown and camped on the ground that the Canadians had previously occupied within the picketed gardens. The officers took over the same buildings where the British officers had been quartered. Colonel Lewis sent a messenger to General Winchester, reporting the victory and General Winchester immediately sent a messenger to General Harrison with the good news. General Winchester’s troops were wild with excitement, demanding to march to Frenchtown at once to celebrate the first land victory of the war. They believed this victory to be the first in a series of victories that would lead to the recapture of Detroit, the capture of the British headquarters at Malden. Despite the American victory, Colonel Lewis held a precarious position at Frenchtown, because everyone knew that the British would use their best resources to keep the Americans from retaking Detroit. The Americans knew that the British and Indians would return soon, and they did.

On January 19, General Winchester, Colonel Samuel Wells of the 17th United States Infantry recruited entirely in Kentucky, and about 300 men marched from his encampment on the Maumee River, arriving at Frenchtown on the afternoon of January 20. General Winchester and the troops crossed the River Raisin and camped in an open field on the right of the forces of Colonel Lewis. General Winchester ignored Colonel Lewis when he said it would be safer for the troops to camp within the picketed enclosure, arguing that the “regulars” were entitled to the post of honor on the right of the position. Then General Winchester re-crossed the river and set up his headquarters at a house more than and mile and a half from the American lines. Colonel Wells was left to command the reinforcements, consisting of three companies of the 17th Infantry and one company of the 19th Infantry. On January 20, Colonel Wells returned to the camp on the Maumee to transact some personal business.

The British, Canadians and Indians Recoup and Return

After the Kentuckians defeated the British and Indians at Frenchtown on January 18, they retreated to Malden, Canada where Colonel Henry Proctor, the Commander of the British forces in the region, rallied and revived them. Colonel Procter gathered a force of about 500 British regular and Canadian militia, 600 Indians under Round-Head and Walk-in-the-Water and six pieces of artillery. On January 21, Colonel Procter led his revitalized force and the army marched to the outskirts of Frenchtown and camped for the night without alerting the Americans to their presence.

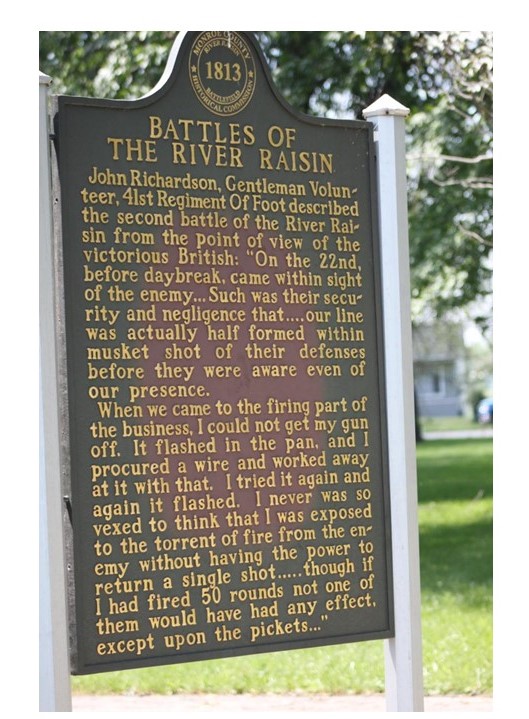

On the morning of January 22,1813, Colonel Procter’s troops were ready for battle, and still undetected. The afternoon before, General Winchester had heard rumors that a great army of British in Indians were approaching from Malden, but he didn’t believe the rumors. He posted the camp sentinels, but he didn’t picket the roads leading into town because of the bitterly cold weather.

The Second Battle of the River Raisin

Near dawn on the morning of January 22, 1813, just as reveille sounded, a force of British troops and war whooping Indians attacked the American soldiers at Frenchtown, showering them with bombshells and canister. They drove Colonel Wells and his regulars camped in the open field toward the picketed camp of Colonel Lewis. General Winchester hastened to the battle field and attempted to rally the demoralized regular troops. A horde of Indians flanked the regular troops who fled across the River Raisin, carrying 100 men from Colonel Lewis’s regiment who had come to support them. Colonel Lewis, Colonel Allen, and General Winchester attempted to rally the men behind the houses and fences on the south side of the River Raisin., leaving Major Graves and Major Madison in charge of the picketed gardens on the north side of the River Raisin. Despite the desperate efforts of General Winchester, Colonel Lewis and Colonel Allen to hold the line on the south side of the River, the American soldiers continued to flee. The Indians flanked them and swarming in the woods along their path of retreat to the Maumee River, they shot and scalped scores of Americans. Nearly 100 Kentuckians were killed and scalped near Mill Creek.

Few Americans escaped, and surrender did not guarantee survival, for in this struggle for land and cultural and political dominance, the Indians were not inclined to take prisoners. In Malden, British agents paid a fixed price for every “scalp lock”, and they had multitudes customers eager for the exchange. American casualties and scalps grew as high as their hopes of victory had been. Colonel John Allen was killed and Chief Round-Head took General Winchester and Colonel Lewis prisoner. Chief Round-Head brought General Winchester and Colonel Lewis to Colonel Proctor who with great difficulty persuaded him not to murder his captives and return their uniforms.

While the British and Indians were defeating General Winchester and Colonel Lewis on the south side of the River Raisin, Major Benjamin Franklin Graves and Major George Madison and their men effectively defended themselves in their picketed camp north of the river. They repulsed fierce British and Indian artillery and musketry attacks and had no intention of surrendering. Kentucky sharpshooters behind the pickets killed the horse and driver of the sleigh hauling the ammunition for the guns and then picked off 13 of the 16 artillerymen serving the battery. At 10:00 in the morning, Colonel Proctor and his forces retreated into the woods and the Kentuckians in the picketed enclosure ate breakfast. While they were eating, they spied a British soldier approaching with a white flag. Major George Madison supposed the British were coming to ask for a truce so the dead could be buried. He and the other Kentuckians were shocked to see Major Samuel R. Overton of General Winchester’s staff carrying the flag and Colonel Proctor alongside him guarding him as a prisoner.

Colonel Proctor had forced his prisoner General Winchester to order Major Madison to surrender at once, assuring him that as soon as the Indians had returned from pursuing and massacring the fleeing American troops they would turn on the remaining Americans and massacre them. Colonel Proctor craftily didn’t tell General Winchester that Major Madison had defeated the British and Indians and driven them back into the woods. Horrified at the bloodshed he had already witnessed and fearing more, General Winchester sent Major Overton to Major Madison with orders to surrender.

The orders to surrender came in writing from his commanding General, but Major Madison refused to obey the orders unless General Proctor guaranteed the safely and protection of all prisoners from violence by the Indians. Major Madison informed General Proctor that the Kentuckians preferred to fight fiercely for their lives instead of being massacred in cold blood. He and General Proctor finally negotiated terms that provided all private property should be respected; sleds would be sent the next morning to remove the sick and wounded to Amherstburg; the disabled would be protected; and that the side arms of the officers would be returned to them when they reached Malden. General Proctor promised to fulfill these terms on his honor as a soldier and a gentleman, but he refused to put them in writing. The Indians began to plunder before the surrender negotiations were finished. Major Madison sprang into action, ordering his men to resist because they hadn’t yet surrendered their arms saving his men from being robbed or killed. The unwounded officers and men and the wounded who could march, were immediately taken to Malden. None of them were harmed.[4]

Massacre on the River Raisin

General Proctor didn’t keep his promise to send sleighs to transport the sick and wounded Americans left in Frenchtown after the battle to the safety of Malden. General Proctor heard rumors that General William Henry Harrison and an American army were rapidly approaching Frenchtown, so he and his white troops quickly left Frenchtown, but the night before he returned to Canada, General Proctor gave his Indian allies a “frolic” at Stony Creek, six miles from Frenchtown on the road to Malden, where he furnished them with plenty of liquor.

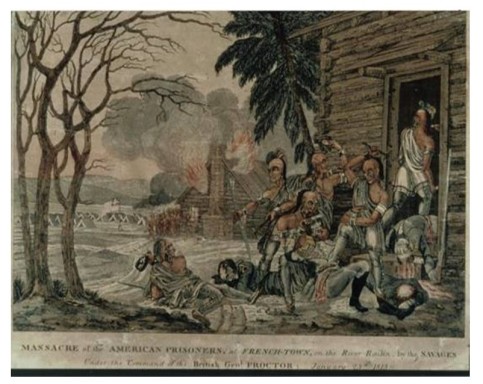

The wounded Americans had no one to guard them from Indian atrocities and no sleighs to carry them to safety. Sympathetic Frenchtown villagers took the wounded soldiers into their homes where Doctors Todd and Bowers, from Colonel Lewis’s regiment cared for them. On January 23, 1813, the morning after the battle, instead of sleighs from Malden, about 200 intoxicated Indians with their faces painted red and black, whopped and yelled their way into Frenchtown. They plundered the village, and then broke into houses containing wounded soldiers. They stripped them, tomahawked and scalped them. The Indians set fire to two houses holding a large number of wounded soldiers, burning them alive, and they tomahawked and scalped soldiers trying to escape through the doors and windows. Outside the houses, the Indians scalped wounded soldiers alive and threw them into the flames. They marched the prisoners who could walk toward Malden, but when they collapsed from exhaustion the Indians killed and scalped them.

Captain Elliott, a False Friend, and the Murder of Captain Nathaniel G.S. Hart

During the massacre, Captain Hart encountered his college friend Captain William Elliott of the British Army. They had been classmates at Princeton, and Captain Elliott had spent months at the Hart home in Lexington recovering from a devastating fever. Now Captain Hart needed the help of his old friend. Captain Elliott promised on his honor to send Captain Hart a sled to carry him to Malden. When Captain Hart reminded him of the promise, his old friend coolly said, “Charity begins at home; my own wounded must be carried to Malden first.” When Captain Hart asked him for a surgeon for the American wounded, Captain Elliott said, “The Indians are most excellent surgeons.” [5]

Although wounded, Captain Nathaniel Gray Smith Hart escaped from a burning house and he was able to travel, so he paid a friendly Pottawattomie chief 100 dollars to guide him safely to Malden. The Pottawattomie Chief Indian put Captain Hart upon a horse, and they started on their journey. While they were still in Frenchtown, a Wyandot Indian claimed Captain Hart as his prisoner and the two Indians argued over the Captain Finally, the Pottawattomie and the Wyandot compromised by killing Captain Hart and dividing his money and clothing between them. Another version of Captain Hart’s murder says that the Pottawattomie Chief tried to defend Captain Hart, but the Wyandot shot and scalped him and yet another version says that the Indians cut off Captain Hart’s head and used it to play football.[6]

Reverend Thomas Dudley, an eyewitness to the massacre, wrote this version of Captain Hart’s murder. He saw the Indians arriving in Frenchtown at sunrise on January 23, 1813, instead of the British with the sleighs to take the wounded to Malden. The Indians ransacked a house where wounded officers were staying and Rev. Dudley watched them murder Captain Hickman and heard Captain Hart talked to an interpreter. Captain Hart asked why Indians were mutilating people and the interpreter said, “They intend to kill you.” Captain Hart begged the interpreter to tell the Indians to stop the killing, but the interpreter said, “If we undertook to interpret for you, they would as soon kill us as you.” Captain Hart paid the interpreter $600 to spare his own life. The interpreter put him on a horse and they began their journey to Malden. A short way down the path they ran into another Indian who demanded the $600 that Captain Hart had paid the interpreter. The interpreter shot Captain Hart off his horse to settle the dispute.[7]

Colonel Proctor ordered all the citizens of Frenchtown to move to Detroit a few days after the massacre and Frenchtown remained deserted for several years.

“Remember the Raisin”

All the troops participating in the two Battles of Frenchtown except for one company of the 19th Infantry “Regulars” were Kentuckians, nearly 1,000 of them. In the defeat and massacre at the River Raisin on January 22 and 23, 1813, they lost 290 men killed and missing and 644 taken prisoner. Out of the entire army, only 33 men escaped being killed or captured. Colonel Proctor reported 24 of his men killed and 158 wounded. There are no known Indian casualty figures.

John Eaton cited some different figures when he estimated that in the second Battle of Frenchtown the Americans lost 397 soldiers with 547 being taken prisoner. The Battle of Frenchtown was the deadliest battle taking place in Michigan and the casualties included the most Americans killed in a single battle during the War of 1812.[8]

The entire state of Kentucky mourned the loss of so many of its young men, but the surviving Kentucky soldiers and citizens gradually replaced the first wave of shock and horror with the passionate battle cry: “Remember the Raisin.”

Nine months after the Battle of Frenchtown on October 5, 1813, at the Battle of the Thames in Canada, American soldiers rushed into battle shouting “Remember the Raisin!” Within an hour, the Americans had destroyed Major- General Henry Proctor’s (he was promoted after his victory at Frenchtown) entire army, although he escaped capture.

Captain Hart Finally Comes Home

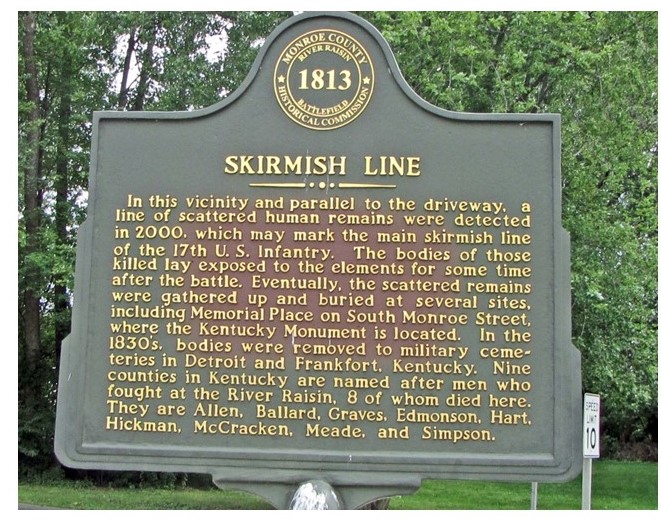

Colonel Richard M. Johnson’s Regiment of Kentucky Cavalry buried some of their fellow Kentuckians a few months later when they marched quickly over the battlefield to another destination. Most of the remains of the massacred Americans weren’t buried until October 15, 1813, when Kentuckians returning victoriously from decimating General Major-General Proctor’s Army at the Battle of the Thames deliberately detoured to Frenchtown to bury their fellow soldiers. They found 65 skeletons and buried them with military honors.

Five years later on July 4, 1818, the remains were reburied in the Monroe Cemetery and in August they were moved to Detroit and buried the Protestant Cemetery there. In 1834, the remains were moved to Clinton Street Cemetery in Detroit and in September 1834, they were once again exhumed, placed in boxes labeled “Kentucky’s Gallant Dead, January 18, 1813, River Raisin, Michigan” and taken to the State Cemetery in Frankfort, Kentucky. Captain Nathaniel Gray Smith Hart is buried in Frankfort Cemetery, Franklin County, Kentucky, along with his comrades at arms.[9]

In 1819, newly created Hart County, Kentucky was named in honor of Captain Nathaniel Gray Smith Hart and some of his descendants still live there.

Over the decades, the State of Michigan designated parts of the original River Raisin Battlefield as a state historic park and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2009, Congress designated the site the River Raisin National Battlefield Park, one of only four such parks in the country and the only one commemorating the War of 1812.

Notes

[1] Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T. (2004). Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 232–23

[2] The Lexington Reporter, January 11, 1812.

[3] Clift, G. Glenn (2009) [1961]. Remember the Raisin! Kentucky and Kentuckians in the battles and massacre at Frenchtown, Michigan Territory, in the War of 1812 Remember the Raisin! reprinted with Notes on Kentucky veterans of the War of 1812 (Reprinted, two volumes in one ed.). Baltimore, Md: Clearfield by Genealogical Pub. Co. pp. 149–150.

[4] Register of Kentucky State Historical Society, Volume 16. Kentucky Historical Society. 1918. p. 59.

[5] Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society …, Volume 10, Issue 31, January 1912. “100 Years Ago – Remember the Raisin” by A.C. Quisenberry.

[6] Ibid.

[7] The Diary of Reverend Thomas Dudley. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moa/ahf3731.0001.001/15?page=root;size=100;view=image Western Reserve Historical Society.

[8] Eaton, John (2000). Returns of Killed and Wounded in Battles or Engagements with Indians and British and Mexican Troops, 1790–1848, Compiled by Lt. Col J. H. Eaton. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. p. 7.

[9] Thirty human skulls and many human bones were exhumed on the battlefield on February 25, 1871 during some excavations and they are believed to be the remains of Kentuckians massacred there and buried by Johnson’s Regiment a few months after the battle.