Sally Ainse used her intelligence, talent, and wit to survive and prosper in both the Native American and white worlds of Michilimackinac, Detroit, and along the Huron River.

Sally Hance Montour Maxwell Ainse, an Oneida Indian woman from Pennsylvania, became a famous fur trader, store keeper, land owner and diplomat before the United States turned 50 years old. She was born on the Susquehanna River in 1728 before America was a country. She died in 1823 when she was 95 years old, well before the Constitution Act of 1867 transformed Canada into a Dominion.

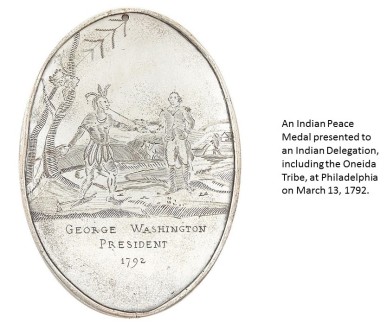

The Oneida Tribe Was a Member of the Iroquois Confederacy

Although she once claimed to be Shawnee, Sally is believed to be Oneida and the Oneidas regarded her as one of their own people. Sally’s Oneida tribe was one of the original members of the Iroquois Confederacy. Like the other Confederacy tribes, the Oneidas had a political and social structure that Sally would use to her advantage and to the advantage of her people. Some sources claim that her surname was Hance, because this was a common name in the tribes in the Iroquois Confederacy.

The Oneida people lived in villages composed of longhouses. Eventually, Sally lived in a house or “mansion”, as she put it, on land that she had purchased herself. Oneida men dominated hunting, trading, and war and Oneida women were in charge of farming, property, and family.

Sally hunted, traded and negotiated between parties in war. Sally developed her leadership skills from within because women always ruled Oneida clans and they made all the land and resource decisions. Men negotiated the trade agreements and chiefs made the military decisions . Sally developed skills in trading and negotiating with military powers as well.

Sally Returns to Her Oneida People

In 1745, when she was just 17, Sally married Andrew Montour, an Indian trader and interpreter for the British and they lived in what are now Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. Andrew was the son of Roland Montour and an Iroquois woman born in a Seneca village in New York and he came from a family of interpreters

There is a conflict of sources about her personal life that unfortunately, only Sally can settle. Some sources say that she and Andrew Montour had several children. Others say that they had just one, a son named Nicholas, who was baptized in Albany, New York, on October 31, 1756. The same conflicting stories swirl around the breakup of their marriage, with some sources contending that she left him and others stating that he returned her and their son Nicholas to her Oneida people.

Whatever the circumstances of their breakup, Andrew Montour became mired in debt and nearly went to prison in the early 1750s. The family split up in 1755 or 1756, and most of the children went to live in Philadelphia. Nicholas must have been a baby when this happened, if he was born in 1756. Sally and her son Nicholas went to live on the Mohawk River in New York State and by 1759, she was an active trader. Her contemporaries still called her Sally or Sarah Montour and her Oneida people gave her a deed to lands in the Fort Stanwix area, now known as Rome, New York.

A Consummate Trader

Between 1759 and 1766, Sally expanded her activities westward to the north shore of Lake Erie. John Porteous records in his journal which is in manuscript form in the Burton Historical Collections in Detroit, that he met Sally Montour on Lake Erie. He noted that she was going “with one boat and some goods to winter at Grand Point.”

By 1767, Sally was trading at Michilimackinac, Mackinaw City, Michigan. Another confusing and conflicting part of her story happens here. At this point people began to refer to her as Sally Ainse. Some sources say that she was married to or at least lived with Joseph Louis Ainse, a Michilimackinac interpreter.

There is also evidence that she lived with a trader by the name of William Maxwell. In the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, the biography of Joseph Louis Ainsse mentions a mixed breed son, “Ance,” who was known as a Chief at the Straits of Mackinac. It is possible that she was the “Mrs.Ainse” of John Askin’s diary at Mackinaw in 1774-1775.

A Woman of Property

The William Macomb ledger for 1775 records that Sally was also called Montour. In 1788, a group of Indian chiefs granted land to Jonathan Schieffelin and in the transaction she is referred to as “Sarah Ainse alias Wilson.”

Between 1775 and 1785, Sally Ainse traded actively and extensively in the Western District. In 1780, according to a list made by Commandant Arent Schuyler DePeyster, two bateau loads of the merchandise ordered by the merchants of Detroit belonged to her.

Sally accumulated large debts with merchants William Macomb, John Askin, and Montague Tremblay. In 1781, her account with Tremblay was over 4,000 dollars. In 1783, she did business with Askin to the extent of almost 4,000 dollars, and in 1787, her account with Angus Mackintosh was for over 1,000 dollars. She had become a person of property, owning two houses at Detroit, and the 1779 census records that she owned flour, cattle, horses, and four slaves.

Trading Relationships

Evidence indicates that in 1785, Sally Ainse had a trading relationship with David Zeisberger, a Moravian minister and missionary to the Native Americans. He recorded in his diary that in May 1787, Sally Ainse was trading with the Moravian Indians on the Huron River and offered to give them a “good strip of her land on the east side of St. Clair.” He established communities in Munsee, in the valley of the Muskingum River in Ohio, and a short lived one near modern day Amherstburg, Ontario.

As an Oneida Indian woman, Sally anise had developed skills in far and goods trading and diplomacy, but she couldn’t change the Canadian Government’s unjust decision.

After trading in Mackinaw and Detroit for ten years and accumulating assets in Detroit for several years, Sally Ainse decided to move to Chatham, Ontario. She was well respected by both whites and Native Americans and accumulated many friends and at least four husbands. She successfully negotiated with Chief Joseph Brant and Moravian Missionary David Zeisberger, and unsuccessfully with the Canadian government for land that was rightfully hers.

Sally Ainse Acquires More Land

In the 1780s, Sally married John Wilson, a Detroit trader, and in 1783 he assumed responsibility for her account with John Askin. In May 1787, she bought some property and moved to the Thames River in Ontario. She built a house on part of her property in what later became Dover Township.

In 1788 the Ojibwa granted Sally a tract of land at the mouth of the Thames River in modern Kent County, Ontario. She continued to acquire land and received a deed from the Ojibwa for an area along the north shore of the Thames River in present day Chatham, Ontario.

After a few years she sold her home and land in Detroit and settled in her new home. She bought more land, three improved farms, an orchard, and a house that she called “the mansion.”

Alexander McKee Disputes Sally’s Claim

In 1789, Sally petitioned Governor Guy Carleton for title to a portion of the land she had bought from the Indians. She claimed a 300 acre parcel that lay within the area that deputy Indian agent Alexander McKee had bought from the Indians for the British government. Sally’s land claims and purchases conflicted with the claims of Alexander McKee and the argument boiled over in 1790.

Sally resolutely contended that her lands were exempt from this treaty, and a number of Indian chiefs and Jean Baptiste Pierre Testard, a member of the district land board present at the treaty negotiations, supported her claim. Alexander McKee, himself a major land owner in the area, denied that he ever intended to exempt Sally’s land and several members of the land board supported him.

In June 1794, Sir John Johnson, the superintendent general of Indian affairs, exerted his influence and pressure on Sally’s behalf and so did Mohawk chief Joseph Brant. Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, outraged at what he felt was the injustice to Sally, ordered that she receive 1,673 acres of prime Thames River land. Sally had clear title to only about 1.7 percent of the land that she had originally petitioned for, but she accepted the offer. Then in 1798, the Executive Council denied her claim and she didn’t receive the land or the compensation. Sally fought the decision for the next 23 years.

Chief Joseph Brant and Chief Agushawa

Even though she was single minded and resolute in pursuing her land claim, Sally Ainse still carried on her trading. She successfully sued several people for small debts in 1792, and when Richard England, the commanding officer at Detroit, tried to prevent the sale of liquor to an Indian gathering at Defiance Ohio,he complained that “Sally Ainse . . . availed herself of the general prohibition, and privately disposed of a sufficient quantity to keep an entire band drunk.”

Sally left no doubt about where her sympathies lay in the struggle between the British and the Americans during and after the Revolution. After Fallen Timbers in 1794, she acted as a messenger between Chief Brant and Chief Agushawa and delivered Brant’s pro-British speeches to Chief Agushuwa on January 26, 1795.

She remarked that she “was the first that ever settled on the aforesaid lands [Thames River at Chatham] before any white people ever thought to settle there, thinking to have it for herself and friends who were Loyalists, and has served his Majesty since and before the late unhappy rebellion.”

Fallen Timbers and the Treaty of Greenville

Chief Joseph Brant wanted to maintain Indian unity against the Americans and commissioned Sally to carry messages to Egushwa and other leaders of the western tribes.

“I am much afraid that your wampum and Speeches will be too little effect with the Indians, as they are sneaking off to General Wayne every day,” she advised Chief Brant in February 1795. Her judgment proved to be arrow point accurate. That month the western tribes signed a preliminary agreement with the Americans.

A coalition of Native Americans called the Western Confederacy and the United States signed the Treaty of Greenville after the Indians lost the Battle of Fallen Timbers. In exchange for goods valued at about $20,000 the Native Americans ceded large portions of modern Ohio, the region of present day Chicago, and the Fort Detroit area.

Mohawk chieftain Joseph Brant did not blame Sally for correctly predicting the outcome of the negotiations.. He stated on June 28, 1795, that “she is one of ourselves and has been of service to us in Indian affairs at this place {Detroit}”.

Sally Loses the Battle, but Continues to Fight

Sally left her land in Chatham in the early 1800s, and moved to Amherstburg, Ontario. In September 1806, the record shows that when she bought a quart of whiskey from John Askin she still lived on her Thames River farm. Askin noted on her account that he didn’t intend to ask for payment.

Still persisting in her claim against the government, in January 1809, Sally petitioned Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore for compensation for her land claim and again the government denied it. In 1813, she finally relinquished her Chatham holdings and continued to live in Amherstburg until she died in 1823.

On May 10, 1824, George Jacob and James Gordon as executors of the estate of Richard Pattinson were granted letters of administration for Sally’s estate, since she owed Pattinson money and had left no heirs or relatives in Ontario.

References

Deeds of Nations, Directory of First Nations, Individuals in South-Western Ontario, 1759-1850. Greg Curnoe.

Michigan Pioneer Collection, XIX, 589.

Michigan Pioneer Collectons, XII, 173.

Louis Goulet’s “Phases of the Sally Ainse Dispute,” in Kent Hist. Soc, Papers and

Addresses, Vol. V. (Chatham, 1921), 92-9

John Askin Papers, Section III, Letters and Papers, 1780-1785

David Zeisberger, Diary (Cincinnati,1885), I,

Native American Women: A Biographical Dictionary, Gretchen M. Bataille, Laurie Lisa.

Burton Historical Collections, Detroit Public Library