Both Jefferson Avenue and the Dixie Highway have been essential to the development of Monroe County and Monroe. Their stories are separate, then equal, and then mingle into the Monroe and Monroe County history mix.

President James Madison Authorizes Jefferson Avenue

Jefferson Avenue’s family tree goes back to 1811, when President James Madison authorized a party to survey and mark a road following the Detroit River and setting aside six thousand dollars to cover the cost of the road. It is fitting that Jefferson Avenue’s roots extend to President Madison, because he was a close friend of Thomas Jefferson, the road’s namesake.

The War of 1812 prevented the Indian road provision in the Treaty of Brownstown from being implemented. At the beginning of the War of 1812, General William Hull built a military road across the Black Swamp near Toledo, Ohio and on to Detroit, but the road was poorly built and could not carry even light traffic. It cost the United States Government over twenty million dollars to move a few companies of soldiers from Ohio to Detroit during the War. Consequently, flour brought fifty dollars a barrel at Detroit and after the army and the War of 1812 had passed, brush and trees soon reclaimed the military road.

The River Road is Resurrected

A few years after the War of 1812 ended, the River Road began a second life. In 1817 the approximately 200 troops stationed at Detroit were put to work opening a road from Fort Meigs on the Maumee River through Frenchtown, now Monroe, Michigan. President James Madison and Congress established the road as a military road 66 feet wide and set parameters to lay it out.

Congress passed a resolution on April 4, 1818, requesting the Secretary of War to communicate programs and prospects for the completion of the military road. Congress requested Major General Alexander Macomb for a report on the military road. On November 27, 1818, General Macomb wrote to the new president James Monroe: “Completed seven miles, Detroit to the Rapids. The road is a magnificent one, cleared of all logs and underbrush. Bridges were built of strong oak framework. One of the bridges on which men are working is 450 feet long. Will complete the bridges first before continuing with the road.”

The specifications called for the military road to be 66 feet wide, but the ax men cut an 80-foot wide strip. About thirty miles of the road were completed and General Macomb sketched it, labeling it “The Great Military Highway.” He sent his sketch along with his report, but almost before President Monroe and Congress had received and read the report, brush and trees had converted the road back to an Indian trail. Settlers living in the area and using the road were not content to let it remain an Indian trial and neither were soldiers from the War of 1812. They urged Congress to continue to build the road eastward and appealed to the civil and military officials in the Northwest to continue the road to bring the region into contact with the rest of the United States. They also believed that extensions of the Military Road would open the Territory to increased land sales and give the farmers and merchants better access to markets for their products.

Governor Lewis Cass demonstrated that an extension of the Military Road could be made a branch of the Cumberland National Road and bring Detroit into direct contact with the capitol at Washington.

Congress Acts to Extend the River Road

Acting on the many appeals for the extension of the Military Road. Congress in 1823 granted land for the construction of a road from the Connecticut Reserve to the Maumee River, finally honoring the fifteen-year-old agreement with the Indians. Congress appropriated $20,000 to improve the road that the soldiers built from Detroit to Maumee and this appropriation was the first grant that the Federal Government had ever awarded for road building.

The Niles Register of October 11, 1823, reported that Father Gabriel Richard, a Roman Catholic Priest, had been elected a delegate from Michigan Territory. Father Richard was well known around Detroit for his efforts at improving roads. At that time his district extended from Detroit to Mississippi.

The Five Great Military Highways Around 1825

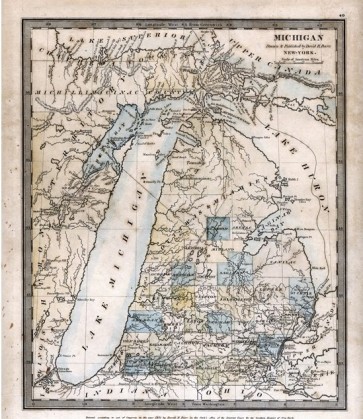

Governor Lewis Cass planned and directed the building of five military highways, called the Five Great Military Highways, in Michigan. These roads radiated in all directions. They were the River Road from Detroit to Perrysburg, Ohio; Michigan Avenue from Detroit to Fort Dearborn in Chicago; the Grand River Road from Detroit to the mouth of the Grand River; Woodward Avenue from Detroit to Fort Saginaw; and Gratiot Avenue from Detroit to Fort Gratiot north of Port Huron.

A map of the Michigan Territory in 1825 shows these roads and they are marked as United States Roads. Although they were laid out as military roads at 100 feet widths, they were used primarily for peace and commerce. The River Road was the only one of the five military roads that served as an actual military road and that didn’t happen until the United States entered World War I in 1917. Then the River Road was covered with huge motor trucks carrying war materials from Detroit to the sea.

On October 29, 1829, the Legislative Council of the Territory of Michigan authorized a lottery to raise funds to build a road between Detroit and Miami in an attempt to help Congress. This was one of the first examples of local officials working with Congress to bring about improved roads. In the following decades, roads including 122 plank roads in Michigan in 1851 were being built across the United States. Plank or corduroy roads (so called because the adjacent logs were as rough and ridged as a piece of corduroy cloth) were built in Michigan although mud could and did cover plank roads. There are still some traces of corduroy on the River Road buried deep in the ground near Silver Creek. Wagons often had to wallow through the mud to make it to market and stage coaches often got stuck up to their rims on the muddy spring roads. In the days before railroads, stage coaches were often the only way people could travel from one town to another.

One of the first stage coach lines to be established was along the River Road to Ohio. Ecorse pioneer Alexander Campau enjoyed the boyhood adventure of riding from Detroit to Monroe and back on the stagecoach which one of his distant cousins drove. He loved the experience of pulling into Monroe at night, hot, dusty and weary and listening to the traveler’s spinning tall tales as he ate supper. The next day arising at dawn to match the stage home, he felt a renewed sense of adventure as he headed to Ecorse along the River Road.

Miserable Macadam and Crass Concrete

The late 18th and early 20th centuries were developing years for macadam, concrete and the automobile. People insisted that macadam and asphalt were bad for horses because they kept falling on macadam and asphalt roads or wearing out their shoes on them. The roads, especially in rural parts of Wayne County, were still impassible during the winter and wet seasons of the year.

The Wayne County Road Commissioners submitted their first annual report to the Board of Supervisors in 1907 and requested an appropriation of $5,000 for the maintenance and repair of the River Road. This was the first step toward developing the rural sections of the River Road and during the following year the Board directed the improvement of the first mile of road. The specifications called for a 15-foot-wide road made of tar macadam to extend north of the north limits of the Village of Trenton in the vicinity of Monguagon Creek.

In 1909, a section of the River Road built of macadam, limestone and crushed cobble was begun at the south limits of the City of Wyandotte and joined to the section built the year before. As the rural sections of the River Road were being constructed, parallel pavement building was also taking place along its length. Workers constructed a brick pavement at River Rouge to join the section of brick pavement already built in Ecorse. Ford City constructed a brick pavement and when this was completed there was a continuous stretch of about 28 miles that extended from the Wayne-Macomb County line to Sibley. There was just one short break in the pavement in the southern end of Wyandotte.

Workers built the first section of concrete pavement on the River Road in 1910. In 1911, another three-and-a-half-mile section extending south from the south limits of Trenton was built. The city of Wyandotte also built a section of brick pavement one half mile long to close the existing gap. The concrete construction was carried on to the Monroe County Line and by the end of 1912 the total mileage of hard surface road amounted to less than twenty miles. Approximately eleven miles were concrete, two miles were tar macadam and seven miles were brick. This provided a continuous stretch of good road from the Macomb County line to the Monroe County line.

From Horses to Cars and Trucks

In the early Twentieth Century road commissioners began to conduct traffic counts on roads or a major intersection to pinpoint traffic conditions. The earlier traffic counts showed a definite trend towards motor vehicles. The first traffic count on the River Road was taken in 1912, just outside the city limits of Detroit. The day long count showed that there were 125 horse drawn vehicles, 370 autos, and 13 trucks. A 14-hour count at the same location in 1920 showed 33 horse drawn vehicles, 1,619 autos and 329 trucks. On July 31, 1927, after the River Road had been widened to 72 feet, the count for 14 hours in the Village of Trenton showed 10,450 automobiles, 73 buses and 31 trucks.

Jefferson Avenue is crowded with history, from the historical houses of Detroit, the automobile and steel industries of River Rouge and Ecorse, and meadow green riverside parks that it passes, as Biddle Avenue, in Wyandotte. Jefferson Avenue touches Elizabeth Park in Trenton and passes historical mansions and hospitals in Trenton and Riverview. It faces Gross Ile bridges, and meanders into rural areas or Rockwood before it turns into the Dixie Highway that continues to Monroe and Toledo and beyond. Jefferson Avenue grew and declined along with the industries and populations in Downriver, and its future growth is still vitally connected with the communities that it serves .

Carl Graham Fisher and the Dixie Highway

The story of the Dixie Highway starts with Carl Graham Fisher of Indianapolis, Indiana, who lived from 1874-1939. Over his lifetime, he pioneered and promoted the automotive industry, highway construction, and real estate development. Overcoming financial and physical problems, by the late 19th century Carl Fisher had immersed himself in bicycle racing and in many facets of the early American automotive industry. In 1904, Carl and his friend, James A. Allison, bought an interest in a U.S. patent to manufacture acetylene headlights, a forerunner to the electric headlights in modern cars. Quickly, the company dominated the headlight manufacturing market across the country and when Carl and James sold their Prest-O-Lite Company to Union Carbide in 1913, they made nine million dollars (about $220 million in 21st century currency.)

Continuing to operate in his home town of Indianapolis, Carl Fisher operated one of the first automobile dealerships in the United States and he helped develop racetracks and public roadways, including the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In 1912, Carl Fisher initiated and helped develop the east-west Lincoln Highway, the first automobile road across the United States. A few years later, Lt. Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower was part of a U.S. Army convey trip along the Lincoln Highway. The young Lt. Eisenhower used the memory of that trip to champion the Interstate Highway System during his 1950s presidencies.

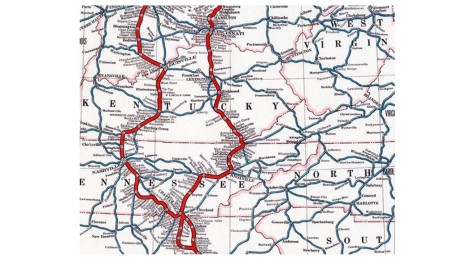

In 1914, Carl Fisher introduced another highway idea, proposing the north-south Dixie Highway from Michigan to Miami, connecting the Midwest with the Southern states. Constructed between 1915 and 1927, the Dixie Highway has reinvented itself in as many shapes and forms as the automobiles that traverse it.

The Dixie Highway Association oversaw the construction, and individuals, businesses, local governments and states provided the initial funding in the highway’s formative years. In the 1920s, the U.S. Federal Government gradually increased its funding of the Dixie Highway and in 1927 the government took over the highway as part of the U.S. Route system. The Dixie Highway Association disbanded and the Federal Government incorporated the Dixie Highway as part of the United States Route system, with some parts of it turning into state roads. Dixie High Routes were identified by a logo with a red stripe and the white letters “DH,” and usually with a white stripe above and below, usually painted on utility poles.

The Dixie Highway’s route inside Michigan followed the present M-129 in Sault Ste. Marie in the Upper Peninsula to Pickford and turned west to make a short jog on former U.S. Route 2, that the Mackinaw Trail has since replaced. The highway crossed the Straits of Mackinac and then used the present U.S. Route 23 and the old U.S. Route 10 to Detroit. It still exists in Michigan as a secondary road from Saginaw southeast to the country line and from southeast Flint to northwest Pontiac and from Flat Rock southwest to Monroe, ending at the Michigan-Ohio Line.

Forks in the Road –Jefferson Avenue and the Dixie Highway

The Dixie Highway follows Fort Street out of downtown Detroit at Clark Street and turns right on West Jefferson. West Jefferson travels through Downriver communities including River Rouge, Ecorse, Wyandotte where it is called Biddle Avenue, Trenton, and Riverview. At the intersection of Jefferson and Huron River Drive just south of Lake Erie Metropark, a right turn leads to the town of Rockwood. A left turn onto Old Fort Road reunites the sections of the Dixie Highway south of Rockwood. The Dixie Highway continues to a diagonal road, U.S Turnpike Road in Berlin Charter Township, the continuation of West Jefferson which branches to the left. The Dixie Highway branches to the right and this stretch of highway passes the Fermi II plant and several small lakeside communities before it goes into Monroe.

In Monroe Dixie Highway turns left onto M-125 also known as South Monroe Street, and crosses the Raisin River into downtown Monroe. The Dixie Highway continues following M-125, Dixie Highway, out of Monroe and to the southwest through farmland and towards the Ohio State line and Toledo.

Jefferson Avenue and the Dixie Highway are highways to the future forged in a historic past.